by Janie Merickel

In February of 2022, CSAR announced its first-ever blog contest, open to both backcountry search and rescue members and non-members. The contest was judged by Matt Lanning of Chaffee County SAR South, Ben Wilson of Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, and Lisa Sparhawk of CSAR. Over the coming weeks we will be posting the winning articles. The following article won third place in the public education category for SAR members. Janie is a dog handler with SARDOC, C-RAD, Summit County Rescue Group and Copper Ski Patrol.

Avalanche search and rescue dogs – avy dogs – are a specialty of the SAR K9 world. These teams train on live subjects and find, without much training, the recently deceased. How they do this is a story of canine magnificence, but it also points to the science behind your dog’s olfactory talents.

Today’s avy dogs are purpose-bred for the work –generally retrievers, shepherds, or border collies – and handlers start bonding with their pups at eight weeks. Leveraging the dog’s desire for hunt, the training includes runaways into ditches and snow caves toward a subject, with an energetic tug as a reward. Gradually, the complexity of the situation grows until the fully trained dog is expected to clear a 100 x 100 yard site, in 20 minutes, with one to three victims buried in the snow.

A recent example of basic avy dog work occurred last year near Jackson Hole, Wyoming. On April 1st, 2021, a pair of skiers went for a ski on Taylor Mountain on Teton Pass. One skier was swept down the mountain in an avalanche and the partner unsuccessfully tried to locate the victim. Teton County SAR was dispatched but had to call off the effort due to darkness.

The next day, an avy dog team from the Jackson Hole was inserted on scene and within minutes found the buried skier, then worked with SAR and the sheriff to complete the recovery.

It’s likely the subject had been deceased for about 20 hours and in two feet of snow when the avy dog arrived and did what it’s trained to do – find buried people. Is it also likely from a Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) perspective that the subject, being cold and dead, didn’t offer a substantial difference from a subject that is warm and alive in a snow cave? Are there enough similarities for the dog to generalize, “Well, this seems good, I might get paid, I’m gonna start diggin”? Seems like it, doesn’t it?

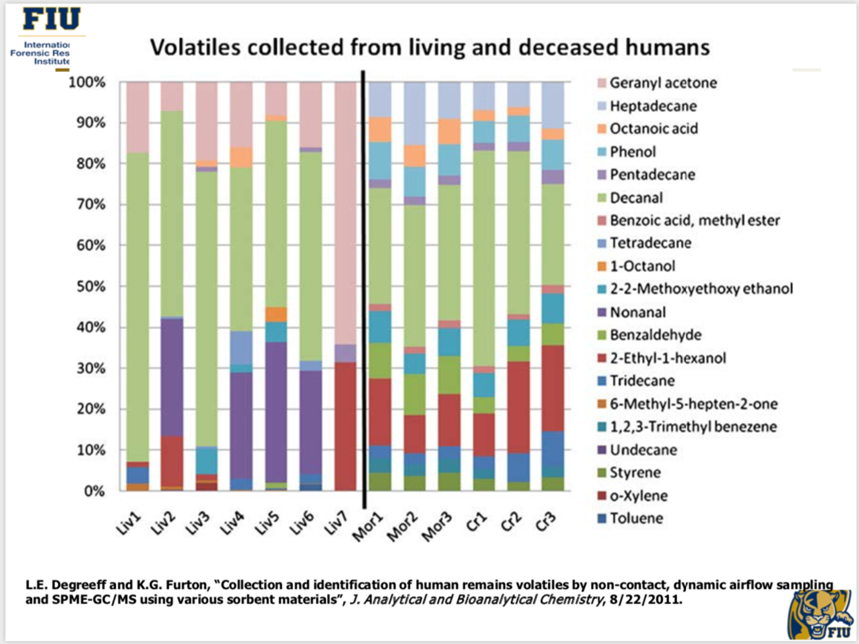

We can pull from a couple scientific sources to answer some of our questions, at least initially. Dr. Ken Furton, of Florida International University, offers research showing different VOCs in humans, alive and then deceased. Sure, there are commonalities, but there also seem to be new VOCs. Sometimes the new mixture creates a totally different odor.

For example, did you know that when you combine the odor of pineapple and strawberry, a human will smell caramel? We know some odors have a primary reaction in the olfaction game – for whatever reason they have a chemical make-up that is more dominate in the nose cells, so they win as the top smell, and sometimes even at smaller concentrations, than other odors present. This type of information and more is available from Dr. Nathan Hall on various podcasts and webinars he has produced with Cameron Ford.

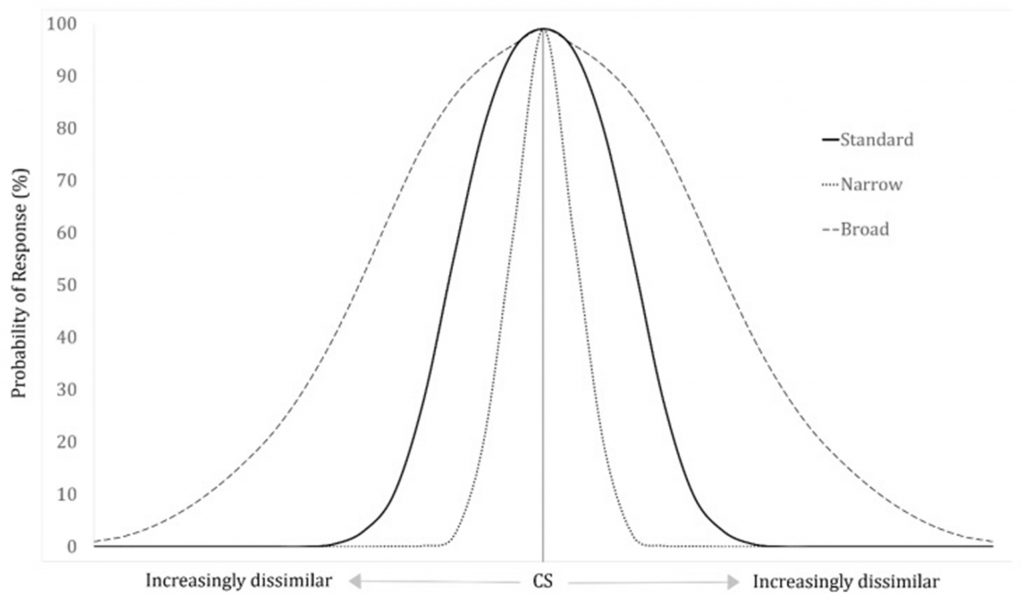

In a 2019 study by Ariella Moser at the University of New England, Australia, she shows the response of trained dogs on dissimilar odor. There are many thoughts on whether this is good or not for a variety of detector dogs, but maybe it’s the key positive factor in what avy dogs have been doing for decades. So, if the conditioned stimulus (CS) here is the live subject in the dog hole, playing an awesome game of tug – then perhaps the deceased are close enough within the bell graph to facilitate their nose getting the job done?

Sure, plenty of avy dogs get imprinted on Human Remains Detection (HRD) odor in trainings, but only a rare few partake in the rigors of wilderness cadaver and HRD certification. The avy dog takes all this in stride, digs on the deceased and helps the community solve the terrible problem of the day.