By William Mundo MPH1,2, Paul Cook PhD3, Laura McGladrey MSN RN3

1 School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, USA.

2 School of Public Health, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, COA.

3 College of Nursing, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, US

In February of 2022, CSAR announced its first-ever blog contest, open to both backcountry search and rescue members and non-members. The contest was judged by Matt Lanning of Chaffee County SAR South, Ben Wilson of Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, and Lisa Sparhawk of CSAR. The following article by William Mundo, Paul Cook and Laura McGladrey is very timely given our current focus on mental health resources for backcountry search and rescue teams in Colorado, and won second place in the technical education category of the contest for non-BSAR members.

What are stress injuries, and how do they look for Colorado Backcountry Search and Rescue (BSAR)?

Backcountry search and rescue (BSAR) incidents are often dangerous. At the same time, BSAR volunteers receive no compensation, healthcare, or mental health services, despite the distinct possibility of personal injury and impacts to mental health from witnessing extreme trauma or death. Professionals working in BSAR are exposed to traumatic events. These exposures regularly lead to increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes, secondary traumatic stress (STS), burnout, and stress injuries.1-5 As these challenges are recently becoming recognized by policymakers, it has become a greater topic of interest. In 2021, the Colorado legislature passed Senate Bill (SB) 21-245, the first bill created concerning search and rescue services in Colorado.6 This bill developed a definition for SAR in the statute. It required implementing a study and stakeholder process to address numerous issues with the existing volunteer-based BSAR system.

One section of the report focuses on BSAR volunteers’ physical and mental health status. They experience taxing work demands with routine exposures to stressors linked to the development of new mental health conditions or exacerbation of pre-existing conditions.1,2,7-11 There is evidence that mental health conditions are significantly higher among first responders than generally.7,10-14 There is also evidence that increased burnout and stress injuries are linked to work-related exposure to trauma in professionals working with trauma survivors.12,13,15-17 Stress injuries are a broad range of psychological and other conditions resulting from duties performed on the job that interferes with a person’s professional and personal life leading to increased risk of mental health conditions. These include anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders.

Despite the health disparities, there are limited interventions for preventing and rehabilitating mental health stress injuries among first responders. Until recently, there was no data to demonstrate the Colorado BSAR system’s mental health status or needs. This article is aimed to discuss the recent section of mental health from the Colorado Parks and Wildlife: Backcountry Search and Rescue Study for the Senate Bill 21-245 (CRS 33-10-116).

How did SB 21-245 collect information about burnout and stress injuries?

Chapter five from the study was a cross-sectional survey of BSAR volunteers in all 64 counties in Colorado. The survey included validated questionnaires and assessed different mental health risk factors, including depression, substance use disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, chronic stress, and burnout. These different questionaries include the Maslach Burnout Inventory, Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale, Beck Hopelessness Scale, and self-reported substance use scales, all of which have undergone psychometric testing and are reliable and valid tools to collect data in similar populations.

What were some of the main findings from the physical and mental health chapter?

There were 657 survey responses and 47 different BSAR teams represented. Briefly, the average age of participants was 47 ± 21. 74% of responders identified as male and 26% identified as female, 96.7% identified as non-Hispanic White, and about 86% had some form of higher education completed. Most respondents were active field BSAR members (64%), followed by BSAR mission leaders/coordinators (18%). The rest of the participants were administrative (1.7%), supervisor (2.4%), board member/officer (10%), and another role (3.2%).

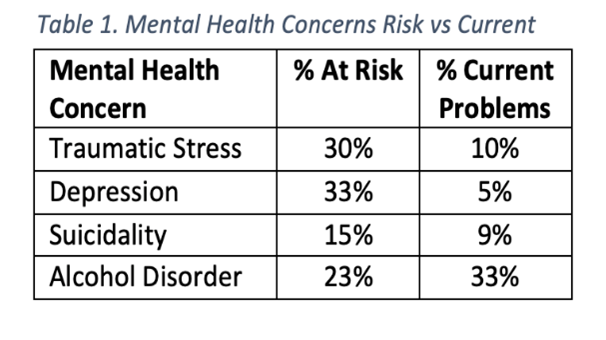

A summary of the mental health disorders BSAR volunteers are at risk for and have current problems with is shown in Table 1.

BSAR volunteers were generally healthy, with 76% reporting either “very good” or “excellent” health. However, 20% of SAR volunteers were at risk for chronic health problems, and 4% were currently in poor health. As many as 1 in 4 BSAR volunteers are experiencing worsening health, and anywhere between 20-25% of the current pool of BSAR volunteers will need to be replaced within the next five years due to medical disability or death.

An early warning sign of burnout is feeling less energized or excited about work. This type of experience is captured by the “positive experiences” scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Lower scores suggest a higher risk for burnout.18 Based on original numbers, 46.8% of BSAR volunteers reported a low level of positive experiences at work, indicating that they are at risk for burnout. Using the adjusted numbers, more than two-thirds (68.6%) of BSAR volunteers are at risk for burnout based on a lack of positive experiences at work.

A second burnout scale, depersonalization, suggests a more severe burnout reaction. People start to see their teammates or the people they rescue as objects rather than people. This reaction is connected to trauma and often occurs among people moving into more severe burnout. In a sample of BSAR volunteers, 31.3% reported experiences of this type. The percentage reporting moderate to high levels of depersonalization, which suggests that burnout is actively occurring, was 12.6% based on raw data or 14.7% based on an adjusted estimate. Participants’ STS survey responses showed that 37% avoid some people or responsibilities related to their BSAR work because of stress. In 8% of these BSAR volunteers, the level of avoidance probably interferes with their work or everyday life. Like the depersonalization scale, this measure again shows that about a third of current BSAR volunteers have some level of burnout. In about 1 in 10 BSAR volunteers, the level of burnout is likely to have meaningful consequences for the BSAR worker’s performance, relationships, or health.

Although BSAR volunteers were hesitant to admit to mental health concerns, they were much more willing to disclose current substance use. The most striking finding was related to alcohol, where 23% of respondents endorsed binge drinking (defined as four or more drinks at a single sitting) at least once or twice during the past year. An additional 33% said they had engaged in binge drinking three or more times. This level of alcohol use suggests that 33% are likely to meet diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder. That level of alcohol use creates risks for mental health problems such as depression and physical health conditions like liver disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

Discussion

To date, this is one of the most extensive studies exploring mental health outcomes and services among SAR volunteers in the country and the first study to explore these topics in Colorado. In a cross-sectional survey among 51 rescue workers, 82% reported being in excellent or very good health compared to 76% in our population.3 In various cross-sectional studies of rescue workers and emergency nurses, on average, they reported a prevalence of between 10-30% of traumatic stress compared to 10% in the Colorado population.12-14,19 In a systematic review by Haugen et al., on average, 9.3% of first responders endorsed barriers to care and need of mental health services4, compared to about 10-30% of the Colorado BSAR population. The data suggest that BSAR volunteers in Colorado may have a greater need than the general SAR population and have a comparable prevalence of traumatic stress to emergency health workers. The level of burnout among BSAR volunteers is slightly lower compared to healthcare workers averaging ranges between 30-70% compared to around 33% among BSAR volunteers in Colorado.15,20-24 Although only 1/3 of volunteers have some level of burnout, about 66% are at risk of developing burnout. High levels of burnout among BSAR may have comparable levels of burnout to health care workers.

The high prevalence of traumatic stress and burnout among BSAR volunteers is of clinical importance. A significant proportion of volunteers may be experiencing adverse effects of trauma, and these symptoms may contribute to emotional exhaustion and increased volunteer turnover.15,17,25 The findings likely underestimate actual numbers given the existing stigma associated with seeking mental health service or admitting to mental health issues. The literature shows that 33.1% of first responders endorse stigma regarding mental health care due to fears with confidentiality and negative career impact, which can potentially lead to underreporting and delayed presentation to care, therefore increasing the risk of chronicity of mental health conditions.4

Given that first responders are at greater risk of experiencing stress, they are likely to engage in substance use as a form of coping and therefore have increased risk of developing substance use disorder. Similarly, in national surveys, it has been found that about 29% of firefighters are at risk of alcohol use disorder, 25% of the police force report hazardous alcohol consumption, and around 30% of emergency responders are at risk of any substance use disorder.26-30 The numbers from Colorado suggest that substance use is similar to other first responder populations though slightly higher, likely given the barriers to access to care for mental health services among our population. The stress and trauma that BSAR volunteers experience daily likely drives professionals towards substance use to cope with the severe psychological harms they encounter.

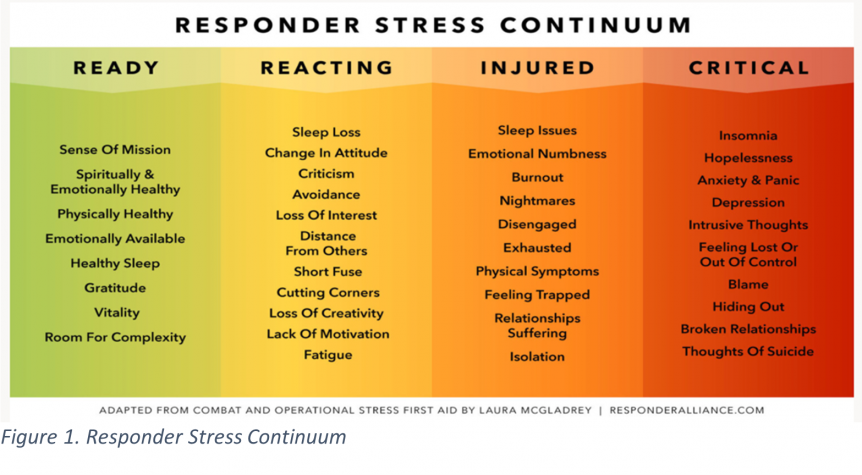

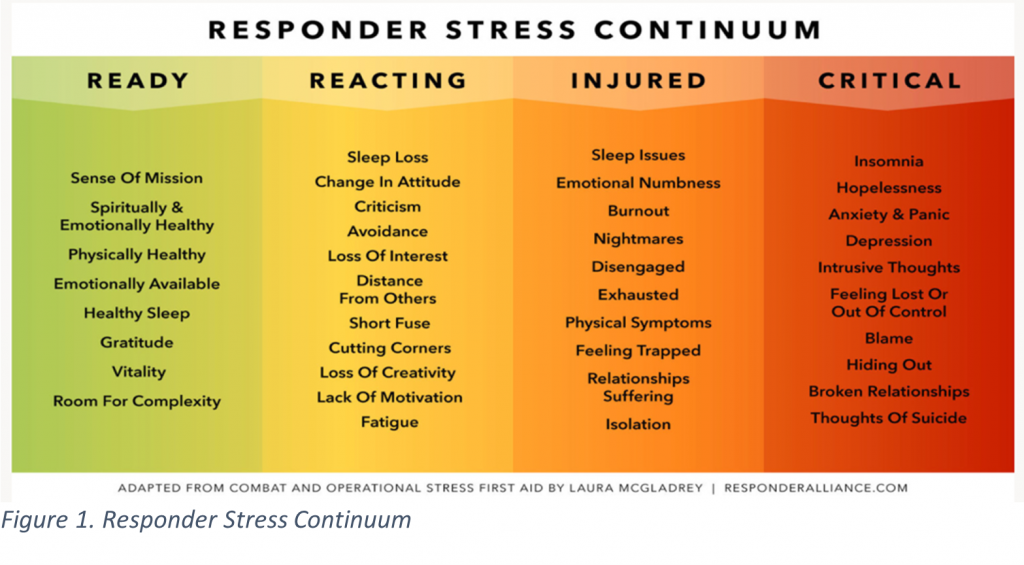

Addressing these risk factors that arise from stress injuries is essential for the productivity and longevity of BSAR teams across the state. One of the main ways to identify and address stress injuries is by raising awareness about the responder stress continuum, which highlights snapshots of how responders are managing stress (Figure 1). By recognizing the different levels, BSAR systems can find specific ways to prevent stress that leads to stress injuries.

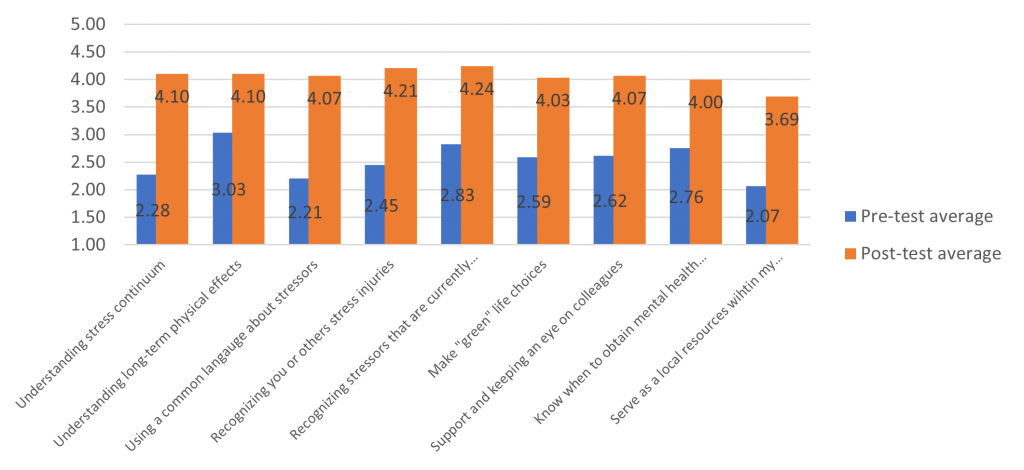

We piloted an online stress injury prevention course and an online support group with BSAR workers in fall 2021. In this writing, preliminary results are available for the first group of 29 participants, with more data expected in spring 2022. The initial group was characterized by a small number of BSAR volunteers with current burnout (13%), but a much larger group with risk factors that suggest an increased chance of burnout soon (an additional 48%). These findings mirror those presented above for BSAR workers statewide and indicate that the pilot participants were representative. Importantly, BSAR workers in this pilot group said they had increased capacity to cope with stress after participating in the program, improving all target learning objectives (all p < .001 in paired pre-post t-tests).

Figure 2. Results of Online Stress Injury Prevention Course

As an overall rating of the course, 86% of participants said the online stress injury prevention curriculum had been either “very useful” or “extremely useful.” Perhaps most importantly, the percentage of BSAR workers who rated their current level of burnout as either high (“orange” level) or very high (“red” level) on a color-coded continuum dropped from 27% to 20% after participation in the brief online course. The effect was strongest for those in the “orange” level of the stress continuum. Still, it was also seen via a slight decrease for those at the “yellow” level of milder stress, which decreased from 31% to 28%, and an increase in those at the least-stressed “green” level from 41% to 52%. Notably, the percentage of SAR workers who already had severe stress injuries (the “red” level) remained constant at 3%. This is a small percentage overall, as it was in the population-level BSAR survey results. But the lack of change for this small group who are already suffering stress injuries suggests that prevention strategies may no longer be effective and that more intensive mental health treatment is likely needed. Therefore, both prevention and formal mental health treatment should be part of a comprehensive solution to meet BSAR workers’ mental health needs.

Conclusion

The effects of stress injuries are of paramount importance to the BSAR system in Colorado as they can increase risk factors that lead to adverse mental health outcomes. The level of burnout and stress among Colorado BSAR teams is comparable to other first-responder groups, including firefighters, police, emergency medical systems, and emergency and critical care health workers. By implementing a stress injury educational course, there is a potential to educate BSAR on how to decrease the level of chronic stress and burnout among their teams.

This article was written by William Mundo MPH, Paul Cook PhD, and Laura McGladrey MSN RN. The Responder Alliance is led by Laura McGladrey, who can be contacted at Laura.McGladrey@CUAnschutz.edu. The views and opinions expressed by authors are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the University of Colorado, Responder Alliance, and the Colorado Legislature.

References

1. Palgi Y, Ben-Ezra M, Essar N, Sofer H, Haber Y. Acute stress symptoms, dissociation, and depression among rescue personnel 24 hours after the Bet-Yehoshua train crash in Israel:the effect of gender. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24(5):433-437.

2. Soffer Y, Wolf JJ, Ben-Ezra M. Correlations between psychosocial factors and psychological trauma symptoms among rescue personnel. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26(3):166-169.

3. van der Velden PG, van Loon P, Benight CC, Eckhardt T. Mental health problems among search and rescue workers deployed in the Haïti earthquake 2010: a pre-post comparison. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198(1):100-105.

4. Haugen PT, McCrillis AM, Smid GE, Nijdam MJ. Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;94:218-229.

5. Antony J, Brar R, Khan PA, et al. Interventions for the prevention and management of occupational stress injury in first responders: a rapid overview of reviews. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):121.

6. Alma A AD, McIntosh M, McGaldrey L, Cook P, Mundo W. Backcountry Search and Rescue Report SB 21-245 (CRS §33-10-116). Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Department of Natural Resources. 2022.

7. Ward C, Lombard C, Gwebushe N. Critical incident exposure in South African emergency services personnel: prevalence and associated mental health issues. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006;23(3):226-231.

8. Forman-Hoffman VL, Bose J, Batts KR, et al. Correlates of lifetime exposure to one or more potentially traumatic events and subsequent posttraumatic stress among adults in the United States: results from the mental health surveillance study, 2008-2012. CBHSQ data review. 2016.

9. Kshtriya S, Kobezak HM, Popok P, Lawrence J, Lowe SR. Social support as a mediator of occupational stressors and mental health outcomes in first responders. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(7):2252-2263.

10. Firew T, Sano ED, Lee JW, et al. Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers’ infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e042752.

11. Berger W, Coutinho ES, Figueira I, et al. Rescuers at risk: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of the worldwide current prevalence and correlates of PTSD in rescue workers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(6):1001-1011.

12. Shah SA, Garland E, Katz C. Secondary traumatic stress: Prevalence in humanitarian aid workers in India. Traumatology. 2007;13(1):59-70.

13. Ratrout HF, Hamdan-Mansour AM. Secondary traumatic stress among emergency nurses: Prevalence, predictors, and consequences. Int J Nurs Pract. 2020;26(1):e12767.

14. Dominguez-Gomez E, Rutledge DN. Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among emergency nurses. J Emerg Nurs. 2009;35(3):199-204; quiz 273-194.

15. Orrù G, Marzetti F, Conversano C, et al. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(1):337.

16. Argentero P, Setti I. Engagement and Vicarious Traumatization in rescue workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84(1):67-75.

17. Greinacher A, Derezza-Greeven C, Herzog W, Nikendei C. Secondary traumatization in first responders: a systematic review. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1562840.

18. Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory – General Survey: An Internet Study. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2002;15(3):245-260.

19. Mealer M, Jones J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the nursing population: a concept analysis. Paper presented at: Nursing forum2013.

20. Bridgeman PJ, Bridgeman MB, Barone J. Burnout syndrome among healthcare professionals. The Bulletin of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. 2018;75(3):147-152.

21. Cieslak R, Shoji K, Douglas A, Melville E, Luszczynska A, Benight CC. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(1):75-86.

22. Ford EW. Stress, burnout, and moral injury: the state of the healthcare workforce. In. Vol 64: LWW; 2019:125-127.

23. Wurm W, Vogel K, Holl A, et al. Depression-Burnout Overlap in Physicians. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0149913.

24. Zborowska A, Gurowiec PJ, Młynarska A, Uchmanowicz I. Factors Affecting Occupational Burnout Among Nurses Including Job Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction, and Life Orientation: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:1761-1777.

25. Jenkins SR, Baird S. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma: a validational study. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(5):423-432.

26. Donnelly E, Siebert D. Occupational risk factors in the emergency medical services. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2009;24(5):422-429.

27. Oehme K, Donnelly EA, Martin A. Alcohol abuse, PTSD, and officer-committed domestic violence. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice. 2012;6(4):418-430.

28. Violanti JM. Alcohol abuse in policing. FBI. L Enforcement Bull. 1999;68:16.

29. Jahnke SA, Poston WC, Haddock CK. Perceptions of alcohol use among US firefighters. Journal of Substance Abuse and Alcoholism. 2014;2(2):1012.

30. Abuse S. First responders: Behavioral health concerns, emergency response, and trauma. 2018.