It was a Tuesday in February of 2011, and three experienced backcountry skiers, all local to the Aspen area, were skiing in an out-of-bounds area in the East Snowmass Creek Valley. On their third run, they exited Snowmass Ski Resort from a backcountry access point off Sneaky’s Run and skied into a steep and rocky area known as Sands Chute.

At the time, avalanche danger was listed as considerable for northwest through east-facing aspects at and above treeline, and the danger was worsened by high winds, which loaded more snow onto unstable slopes. The three skiers were wearing avalanche transceivers and carrying probes and shovels, and they skied the chute one at a time, as they should have. It didn’t matter, however. The avalanche that struck the second skier and carried him down the chute must have killed him very quickly, because his friends found him and uncovered his head within about five minutes, and their efforts at CPR were not successful.

It was late in the afternoon when the two friends skied out and called for help, so the decision was made to delay the recovery until the next morning. But Wednesday morning, members of the ski patrol and Mountain Rescue Aspen, as well as Brian McCall, local forecaster with the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, decided conditions were still too unstable. Sheriff Joe DiSalvo said, “I will not risk rescuer’s lives at this point.” Brian McCall said, “I’ve been to a lot of accidents and I haven’t seen any terrain this complicated … or dangerous.”

A second slide in Sands Chute that Thursday moved the body about 200 feet from the original location and stymied plans for a Friday recovery. The body was finally recovered the following Tuesday, a full week later, by a team of rescuers from Mountain Rescue Aspen and Snowmass Ski Patrol, using avalanche dogs and a helicopter from DBS Helicopters of Rifle to assist.

The coroner’s final determination on cause of death was asphyxiation. Being experienced, well-equipped and able to find a buried subject within five minutes does not always make a difference in the outcome.

That was not the only avalanche fatality in the Aspen “sidecountry” that year. Another skier was killed in April of that year after exiting a backcountry access point from Aspen Highlands. There have been many Colorado avalanche accidents involving skiers leaving a backcountry access point over the years, and just recently, in December of 2022 there was a fatality in the backcountry adjacent to Breckenridge Ski Resort.

Since the 2009/10 season, the CAIC reports a total of 85 sidecountry avalanche accidents, 10 of them resulting in a fatality. Since that season almost 16% of fatal avalanche accidents in Colorado occurred when people left a ski area to recreate in the backcountry. People often call backcountry areas accessed from a ski area “sidecountry,” but what does sidecountry really mean?

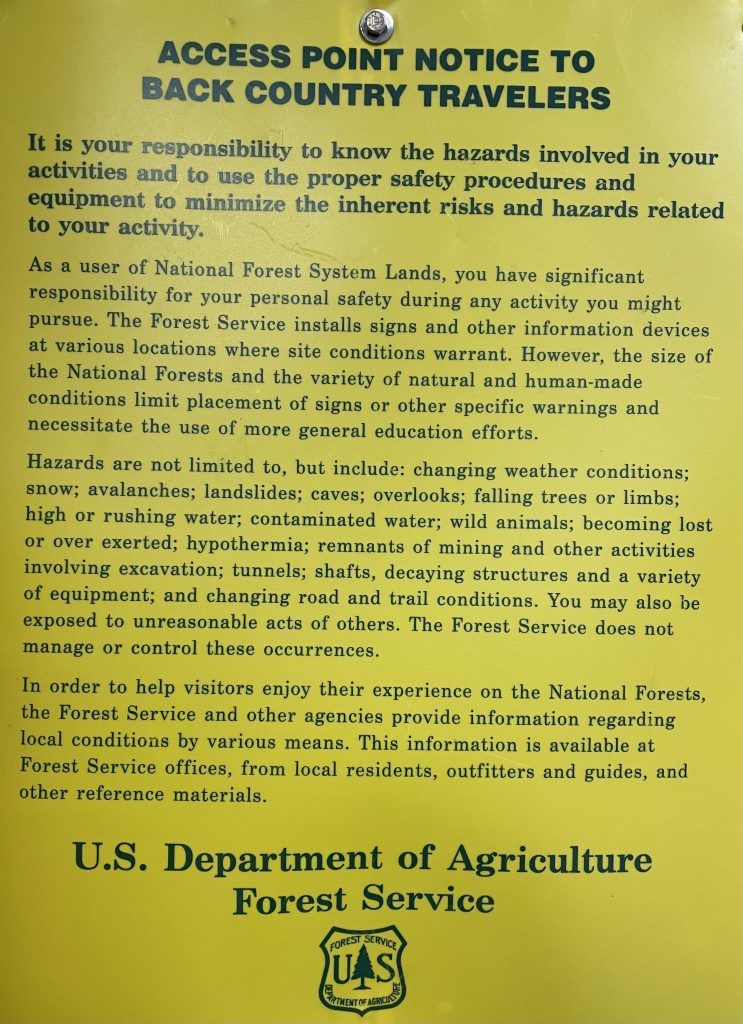

The backcountry terrain adjacent to a ski resort and accessed through a backcountry access point is often called sidecountry. A backcountry access point from a ski area in Colorado is something discussed and agreed upon between a ski area’s management team and the U.S. Forest Service. When there is an interest to designate a new access point, the ski area proposes the point in their annual operating plan and the USFS approves it. The two primary goals are to provide reasonable opportunities for recreational access to public lands, and to provide public education on the risks of using these access points.

It is rare that a backcountry access point is ever closed; it generally only happens when a ski patrol recommends a temporary closure due to ongoing rescue operations that could be endangered by the presence of backcountry recreationists . A USFS forest supervisor would then make the decision to close an access point, and ski patrollers would staff it to enforce the closure.

It’s easy to be fooled into thinking that sidecountry terrain is somehow safer than the backcountry terrain accessed from a trailhead. It’s so easy to access, it’s right next door to the ski area, and perhaps there are many other skier tracks visible; all of this tricks us into thinking it must be safe. David Boyd, public affairs officer for White River National Forest, comments, “Even though these access points are relatively easy to get to, it’s like anywhere else in the backcountry where there is no avalanche mitigation work and it’s up to the user to track avalanche conditions, understand the risks, and have the proper equipment.”

Why don’t backcountry access points close during periods of high avalanche danger? Don Dressler, mountain resort program manager for the USFS, explains, “Closing a backcountry access point due to avalanche danger is a slippery slope, because then when it’s open people will think it must be safe. There are always hazards in the backcountry, and the goal is to educate users to assess and mitigate those risks on their own.”

Until 2011, Summit County had a much more restrictive boundary management policy than Eagle and Pitkin counties due to the deadly avalanche accident on Peak 7 in Breckenridge in 1987 that killed four skiers. But pressure to create more access points mounted because of problem areas where skiers were frequently ducking ropes. By placing access points in areas where people were cutting ropes illegally, skiers and riders leaving the resort would at least have to pass by warning signs informing them about the potential risks, including avalanches.

Dale Atkins, member of Alpine Rescue Team and a former CAIC forecaster, comments, “Studies tell us the problem with warning signs is not that people don’t read them, but rather that they don’t think the warnings apply to them.” Proximity to the ski area and the tracks of other skiers can make people consciously or subconsciously assume the area must be safe and the warnings are not to be taken seriously.

Avalanches are not the only potential hazard involved in leaving a ski resort through a backcountry access point. Snow immersion deaths – in which a person suffocates after falling into a tree well, a gap next to a rockface, or just into very deep snow – is also a concern. One snow immersion death has happened already this winter, outside the Vail resort boundary in East Vail.

Routt County Search and Rescue (RCSAR) also reports a number of incidents involving stuck, lost and hypothermic skiers who needed rescuing after leaving Steamboat Ski Resort through an access point. Just recently, in January of 2023, RCSAR members spent eight hours searching for a lost skier who eventually self-rescued. The skier was lost after skiing through an access point from Tomahawk run that leads to Holy Bowl. Unfamiliar with the area, he continued down a path that led him even farther away from the resort, and finally made his way out at Alpine Mountain Ranch at 11:00 pm that night. “He got extremely lucky because he went through some serious terrain and avalanche conditions,” says Jay Bowman, president of RCSAR.

The bottom line? Sidecountry is backcountry. Be prepared by reading the avalanche and weather forecasts, paying attention to warning signs, doing your homework on other potential hazards, and skiing with avalanche equipment you know how to use and a buddy who can say the same. It’s about living to ski another day.