By Luke Mielke, Douglas County Search and Rescue

Please! Please! Please! Don’t self-diagnose. This stuff is complicated, with lots of gray areas. Far too often, mental health conditions are referred to in casual conversations and we don’t want to be discrediting how serious and life-impacting they can be. The good news is, psychological stress injuries can be recognized early, addressed before becoming worse, and effectively treated with professional mental health help.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5-TR) defines trauma as, “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.” The manual also states this exposure can occur either through directly/personally experiencing the event, witnessing the trauma occurring to another person firsthand, or being exposed repeatedly to the details of traumatic events (SAR-related examples might include arriving on scene to a trauma patient, body recoveries, multi-day or complex missions, etc.) (Pai et al., 2017). The DSM-5-TR is what clinicians in America use to inform official mental health diagnoses. As search and rescue personnel, we may experience exposures to traumatic events, but it is rare. We certainly do high-risk things, but we train to do them as safely as possible to reduce exposure to actual or threatened personal death and injury. However, we often see other people seriously injured, perform body recoveries, and experience high-stress/complex rescues. Sometimes, tragically, we do everything we can and our patient still dies. These events can be very traumatic and stressful. Experiencing a traumatic event is what puts us at risk of developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) if unaddressed, but it doesn’t mean that if we experience these things, we will develop a diagnosable mental health condition.

You may have heard people using terms like PTSD, burnout, stress injury, moral injury, and acute stress disorder. These terms can be complex, and rather than define them all for you here, I am more concerned with describing the importance of recognizing when we are impacted by a stressful or traumatic event we experience in SAR and doing things to take care of ourselves after an exposure to help us continue serving our communities as SAR members. To simplify language and remove confusion that can be caused by formal definitions, the Marines developed the Operational Stress Continuum Model; this model is being applied more and more in first responder contexts. (United States Marine Corps, n.d.).

The stress continuum has four levels: green, yellow, orange, and red. If you apply the continuum to a physical injury, green would be healthy/functioning, and yellow might be a scratch or small cut. The orange is when that cut may becomes infected if it isn’t cleaned and treated. The red category is where you might see sepsis or more serious illness and difficulty functioning. This could be the progression if nothing is done to treat that tiny cut. By applying the continuum to mental illness, we can start to understand how stressors big and small can progress to a psychological injury (red zone) if we do not recognize or are not doing anything to address and treat the psychological impacts of the traumatic exposure. The good news is, we can intervene at any point in the continuum by doing things that help us return to the green zone. Sometimes we can get back to the green on our own, sometimes it requires the help of friends and family, and at times it requires us getting assistance from a mental health professional. .

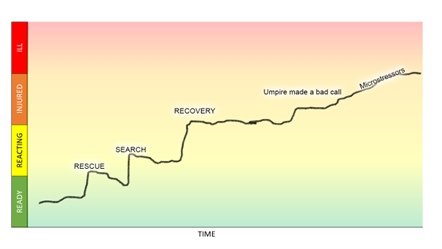

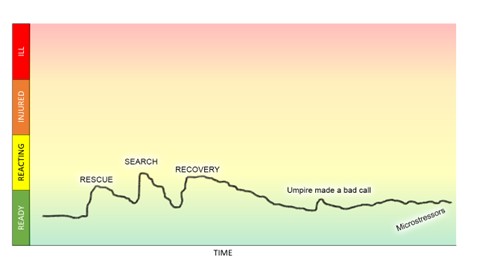

Consider the following search and rescue volunteer scenario. Chris is married with two children and has been on a team for over five years. One weekend, after a long week at work, he assisted in a search that ended in a body recovery and an additional rescue. He then went to his child’s baseball game, went shopping for groceries, and had to complete a presentation for work on Monday. Each of these factors can produce stress in Chris’ life, depending on many psychological factors, the outcome of which depends largely on his coping strategies, physical health, social supports, and help-seeking behaviors, among other factors. If these stressors are not addressed or mitigated, they can accumulate over time and lead to stress injury or even illness (Metz, 2022).

In picture form. The graph on the left illustrates stress accumulation without any self-care or assistance. This is when we might see someone scream at a cashier for no apparent reason; they have reached their limit. The graph below, on the other hand, represents good self-care and accessing additional supports when needed.

We call these “green choices,” or things we can do when we realize we have been impacted by stress that help us return to the green zone. These green choices can include reaching out to friends, family, peer supports, and professional mental health help if you find yourself in the red. Other green choices can include getting good sleep, physical activity, eating nourishing foods, and engaging in our preferred activities and hobbies. Undoubtedly, significant stressors come up in SAR and in life, and sometimes we may need help to get back to the green and to being ready. A worksheet is available on the stress continuum, and another to help you identify how you personally can stay in the green. We plan and prepare for complex searches or rescues through trainings, continuing education, and buying way too much gear to do what we do better; having a self-care plan is another crucial thing we need to do as SAR members in order to stay mission-ready.

If you or someone you know is experiencing a

mental health crisis dial 988.

Luke Mielke recently retired from the military and started working with Code-4 Counseling and the It’s A Calling Foundation. He has completely shifted careers to provide mental wellness support and training to the first responder and military community. If you have any questions or need additional resources, message him at luke.mielke@code4counseling.com

Reviewed and edited by Kristen Griffin,Summit County Rescue Group. Kristen isa Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) and Licensed Addiction Counselor (LAC) in the state of Colorado. Kristen specializes in the treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and anxiety disorders, and has experience treating trauma and stressor related disorders. She is trained in evidenced based modalities such as Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) to treat psychological stress injuries.

Metz, S. (2022, February 4). Conversations around stress must move beyond “I’m fine; how are you?” Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/conversations-around-stress-must-move-beyond-im-fine-how-are-you

Pai, A., Suris, A., & North, C. (2017). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations. Behavioral Sciences, 7(4), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010007

United States Marine Corps. (n.d.). THE STRESS CONTINUUM DISCUSSION LEADER’S OUTLINE. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.iimef.marines.mil/Portals/1/documents/PWYE/Toolkit/MAPIT-Modules/COSC/The%20Stress%20Continuum.pdf