By Mark Sokol

In February of 2022, CSAR announced its first-ever blog contest, open to both backcountry search and rescue members and non-members. The contest was judged by Matt Lanning of Chaffee County SAR South, Ben Wilson of Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, and Lisa Sparhawk of CSAR. The following story by Mark Sokol won second place in the mission story category for non-SAR members.

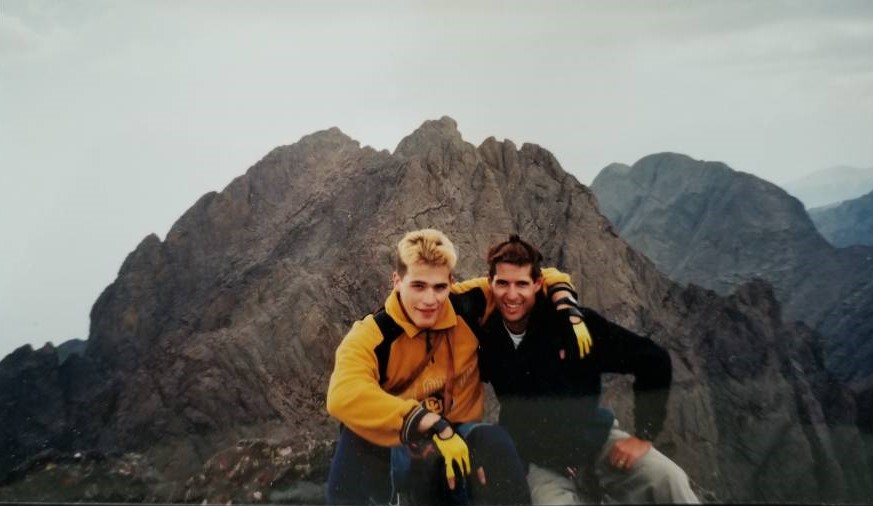

Crestone Needle is one of the most difficult 14ers to climb in Colorado, and also offers one of the fifty classic climbs in the nation: the Ellingwood Arête. One fine day in 1996, my friend Corey Scott and I decided to climb this route. I had been eyeing the route for years but never had anyone I could convince to go with me.

Corey and I had climbed together many times in the past and were very comfortable climbing partners. I was at the time a confident 5.10 lead climber and Corey was a solid non-lead 5.10 climber. The Ellingwood Arête is classified as a hard 5.7, so we had picked a route that fell well into our ability as climbers. The only potential problem was that Corey would not be doing any of the lead climbing, so I would have to take that responsibility.

Neither of us had been on the route before. I had read as much as I could find about the route, and talked to others who had climbed it to compile as much beta as I could. I also had been in the region many times before and knew the approach very well. It started about seven miles down the mountain at a jeep trail just outside of Westcliffe, Colorado. With my 95 Wrangler loaded to capacity, Corey and I bounced up the increasingly rough road to its closure about a mile and a half below South Colony Lake. We parked the jeep and carried our immensely heavy packs (loaded with a full rack of climbing gear, tents, sleeping bags and food) for the short mile and a half to a spot just below the lower lake. We made camp, ate dinner and got to sleep. We figured we could get a good start around 7am.

This turned out to be one of our biggest mistakes. Since this time, I have learned a great deal about how to climb a major route, when to start and how to be successful. We should have started before sunrise to give ourselves an ample chance to make it.

We started the next morning ready to go. We began a high traverse several hundred feet above our camp and worked our way at an angle up to the Ellingwood Arête. This was mostly 3rd and 4th class, hand over foot, easy climbing. The exposure intensified dramatically with every step; there were 1000-foot drops to the rocks below. This was my (and Corey’s) first experience with such exposure at a moderate climbing difficulty level. Because of our discomfort we decided to rope up early in the climb; we were climbing, roped, over relatively easy 4th class stuff. In retrospect, we should have waited until we got to the main headwall at about 13,800 feet before we roped up. This would have saved precious time.

We made the ridge and worked our way up to the main headwall as slow as snails. The entire time, however, was exhilarating and incredibly exciting. We were in a beautiful basin surrounded by high peaks. The rocky ridge loomed high above and the sheer immenseness of the mountain swallowed us up. To be completely encompassed in such an environment is an addictive feeling that builds upon itself and grows the more you do it. The rocks under our feet fell rapidly away and disclosed glimpses of the lake over a thousand feet below. The reassurance of the rope was both a tremendous comfort and a grim reminder of the slow pace at which we were traveling.

After a long morning and short afternoon, we reached the base of the headwall at around 13,800 feet. We were already roped up so there was no real reason to hesitate, but we stopped anyway and had some food. We felt good despite our slow pace. We felt like we could make the summit in two hours, then descend to our tent below in another four. It was late September, and there were no storms forming. We felt pretty confident that the weather would hold.

I looked at the route before me. A chimney opened up above me and split the face of the headwall, revealing a weakness. This was my route. We set a belay station for Corey, and I stepped up into the crack. “On belay?”

“On belay dude!”

I reached up above me and grabbed a knob of rock. It looked like it could just break off in my hands, but it was solid. Such was the consistency of the conglomerate, volcanic rock of the Sangre De Cristo Mountains. About 20 or 30 feet into the chimney I came across an old piton. I clipped into it for a laugh and then placed my own cam next to it. I wedged and pulled my way up through the rocky chimney until the vertical walls around me gave way to an angled slope that went up and around to another ledge at the base of the second headwall. I set my belay station here and called down, “Off rope!”

A few minutes later Corey called up and was ready to climb. As I sat in my belay stance recouping a bit from the excitement of my first pitch of climbing at altitude on a major peak, I looked out at the peaks around me. To be in such a place sometimes takes a great deal of physical effort. One can, at times, forget to look around and realize where you are. The view around me was far beyond breathtaking. I could see Humboldt Peak across from me and to the east. To my left was a wide-open saddle where three major peaks all come together. This huge saddle is known as Bear’s Playground. Kit Carson looms above this area to the west. To my right, the terrain fell away from South Colony Lakes into the trees and the Wet Valley.

Before I knew it, Corey was up the pitch and next to me on the ridge. “Having fun? I asked. “Hell ya!” was the always enthusiastic response. It was time to start the next pitch, so Corey and I traded places, and he clipped into the anchor and prepared to belay me as I led up. This was the point of the climb where I had some doubt from the start. I wasn’t sure exactly where the route was supposed to go. The guidebooks I read all described a route up and to the left of the headwall. There was supposed to be a chimney of 5.6 climbing or so that led to a spot above the 150-foot section. There seemed to be a route directly up the headwall as well. This, as I recall, was rated as a 5.8 direct approach. I couldn’t really see around the corner but decided that 5.6 was a safer bet than 5.8, and it was kinda getting late. I stepped out left onto a 60-degree slab of rock that angled up to a chimney system. There was an overhanging crack right above me, and a possible depression further around the corner. I was already out of sight of my belayer and the overhang didn’t look that bad. If this was the correct route, then it couldn’t be harder than 5.6, I was thinking.

I placed a cam at the base and went for it. There was a solid 15-foot section that I felt good on and as I hung out over the slab, I knew that I could make one or two more moves and secure the overhang and then place a cam. Holding on with my right hand, my right foot jammed in the crack, I stretched up, left toe placed for balance on the opposing face, for an apparent hold just above my head. As I placed my hand on the shelf, I expected a nice deep handhold, but was completely let down. Instead of a deep hold, it was a deceiving “sloper” that angled down and gave little or no resistance. I mistakenly placed too much trust in this hold and when it didn’t support my weight, I peeled off the rock. I didn’t even have a chance to say anything before I was airborne. My right foot, which was so well placed in the crack, ripped out and I felt a pop in my knee. My last cam was a good fifteen feet below me. I had to fall fifteen feet to the cam, then another fifteen for the rope to catch me.

Fortunately, Corey is one of the best belayers ever, and he caught my fall, totally blind, and stopped me before I grounded on the slab. “I gotta come down!” I shouted. He lowered me to him and asked, “You ok?” Unfortunately, I wasn’t. I couldn’t put any weight on my right leg. “No, man, can you lead this?” I asked.

I’ll never forget the look of fear I saw in his eyes. “No way, dude, what do we do?”

Well, I never really thought of that. We couldn’t go down the way we came, because we simply didn’t have enough gear to leave behind to make a descent like that work. (In retrospect, that’s exactly what we should have done.) I couldn’t continue up, and I didn’t know what the descent down the back side would be like. I wasn’t sure if I could even get down the backside once I got to the summit. That’s when I remembered my cell phone. I could see Westcliffe in the valley below and I thought, just maybe, I will have a signal… Sure enough it was a strong signal. I dialed 911.

“911, please state your emergency.”

“I am trapped on Crestone Needle with my partner, I injured my leg and we can’t get down. We need rescue.”

“So, you are where now?”

“Crestone Needle. The 14,000-foot peak just outside of Westcliffe…”

It took a while for the dispatcher to realize what the call was about, but when she did, she connected me to Custer County Search and Rescue in Westcliff. They asked first if my injuries were life-threatening. I wanted to say yes, but I told them no, it’s just that my leg is immobilized. They told us to settle down for the night and get comfortable, and they would begin the rescue efforts and get a team out to us by morning.

It was around 4pm at the time, so we realized there was no way to get anyone up there any earlier. They mobilized a high mountain rescue team from the Evergreen area outside of Denver, Alpine Rescue Team, and sent a team of their own members to South Colony Lake right away. In the meantime, Corey and I settled down for the night. We were standing on a ledge about 10 feet wide and 25 feet long on the cliff face, at about 14,000 feet. We could see our campsite 2000 feet below us. All we had to keep us warm were Gortex shell jackets and pants, and no bivy sack. We were going quick and light and when we started and had no plans of staying overnight up there.

We tied ourselves into the belay anchor and piled the rest of the rope under us for insulation. There were no storms moving in that night and it was clear and cold. Very cold. It was late September and even though there was no bad weather, the air temperature dropped to the single digits. Around 11pm we could see headlamps moving near our campsite. We knew that the rescue team had arrived. I had a head lamp with me, and we flashed S.O.S in Morse code until we got a response from the rescue team below. At least now, they knew our position on the mountain. The team’s plan was to come up the backside of the peak and drop down from the summit to our position. I had been in communication with the Custer County SAR team leader on my cell phone before my batteries went dead. In good conditions, with plenty of daylight, the climb up the backside, the standard route up the Needle, is difficult at best, and would take at least six hours. These guys had to do it under moonlight with headlamps, 3rd and 4th class climbing for 2000 feet in the bitter cold and darkness. It actually kinda sounds fun in a sick sort of way. They probably got started around 2am or so.

In the meantime, I experienced the longest 16 hours of my life. I shivered uncontrollably for most of the night. I was chilled to the bone. It was a combination of being injured, being at high altitude, and the single digit temperatures that brought my body temperature so low. I have sleep apnea, and being at high altitude complicated things even more. I would fall asleep, then stop breathing. Every time this would happen, Corey would give me a hard jab in the ribs to wake me up; “Breathe, man!”

In the daylight, the surroundings are beautiful. I remembered, just nine hours earlier, looking out over the landscape and feeling content. Now as I looked out there was an eerie feeling of dread and heavy darkness. My injuries combined with my situation were probably not life threatening, but at the time, they felt that way. I was scared, for myself and for Corey. It was going to be a long night, and we just had to tough it out and survive.

I remember how excited we were when the first signs of daylight brightened the morning sky and changed its hue from black to a dull gray. The sun was on its way, but her warmth was still a long way off. It seemed like forever, but the sun finally did make it over the horizon. Moments later, we began to warm up. We still had a little bit of water with us, but no food. We knew the rescue team had to be close to the summit by now; it was 8:30am. That’s when we heard voices coming from below us. It was confusing, because we thought the rescue was dropping down from above; we didn’t think they had sent a team up from below. Two climbers popped up in front of us, a man and a woman. “Hey you must be the guys that were stranded.”

These two were just out for a climb and not a part of any rescue effort. They made it to our high point by 8:30am; SIX hours earlier than our time. They started around 4am and had made great time. It was a glaring example of how this route should be climbed, although we were so glad to see other people that these thoughts never really came to mind at the time. The woman gave me her wool hat (I was still shivering uncontrollably) and pulled out the most beautiful pack of Fig Newtons I had ever seen. Nothing has ever tasted better. She happened to be a physical therapist from Boulder, and she took a look at my leg. She correctly assessed that I had torn some ligaments (my MCL). They were micro tears that in the long run didn’t need surgery, but were extremely painful and immobilizing nonetheless (unless you are a pro football player with a bunch of drugs on the sideline to get you through the game).

They continued their way up and said they would tell the rescue team our exact location. Less than 30 minutes later, a guy came rappelling down from above. He took a look at my leg and gave me two options. “You can wait here another two hours for the litter and we can drag you up, or you can try and prusik up a fixed line to the team members above. There is a helicopter waiting on standby in Westcliffe that will be able to pick you up on the summit.” What glorious news! I decided that I did not want to be on that mountain any longer than I had to be so I opted to bite the bullet and do the climb, right up the 5.8 face that we should have done in the first place.

Every time I put weight on the leg, pain shot up my spine. I warmed up pretty damn quick from that. It was nothing short of an epic struggle for me. I was completely exhausted and in terrible pain, but I managed to drag myself up the last 300 feet of the climb with the help of the fixed line and the encouragement of the upcoming helicopter ride to safety. I crested the summit ridge and was greeted by about eight rescuers on the summit. One guy gave me the best tasting bagel I had ever eaten. The guy on the summit said a Blackhawk helicopter from Fort Carson was on its way up the mountain.

I thought about Corey and the difficulty I had ascending that last pitch. I knew that he had a choice of climbing alone on a top-rope belay or ascending using prussiks like I did. I radioed down to him and said, “Corey that was tough, you might wanna consider using the help of the rope.”

“Suggestion noted!” came the reply in his best Homer Simpson voice. He climbed it on his own using the top-rope and in good form. The unfortunate thing is that he had to make the long trip down the backside and to the tent so he could get my Jeep and drive it out. They wouldn’t let him ride in the helicopter with me because he wasn’t injured.

The helicopter had to circle a few times to burn enough fuel to make up to the summit, because of the thin air. We all got down low to the ground, as this Army Blackhawk helicopter rested one wheel on the summit of the peak. Crestone Needle is named so for a good reason. The actual summit is not much more than 10 feet by 10 feet, a tiny needlepoint compared to the rest of the mountain. The piloting was nothing short of remarkable to get a touchdown on such a landing zone. That’s when this G.I. Joe looking guy came out of the helicopter with his helmet and headphones and shouted, “Stay low, and grab on to everything you can!”

“O.K.!” I shouted back, as I watched rocks just hop up and blow right off the summit from the wind generated by the helicopter blades. As I approached the big sliding door of the helicopter, I saw a man inside waiting for me like a catcher in a baseball game. The Army guy behind me gave me a toss and I leapt from the summit into the helicopter as it hovered along the edge. The guy inside caught me and rolled back and clipped my harness to a ring in the back of the chopper, all in one motion. We circled around the mountain a few times because I guess there was a suspicious backpack in one of the couloirs, and they wanted to make sure it wasn’t a body. It gave me an opportunity to see the mountain from a perspective that I may never get again. I saw the entire route, our ledge from the night before and the summit with all the people who went so far out of their way to rescue Corey and me. I was extremely grateful to be so lucky.

The helicopter made its way down to Westcliffe and before long, I was in an ambulance on my way to the local hospital. They put me on oxygen and gave me a warming blanket. I was hypothermic and very low on oxygen. My body temperature was 95 degrees and my pulse/oxygen content was 79 percent. This was after I warmed up a little from the night before, and had gotten down to an altitude with much more oxygen.

The next step was to wait for Corey to get down with the rest of the rescue team and wait for someone to pick us up and drive us home. We survived our ordeal because we were lucky. We called search and rescue and those selfless volunteers saved our asses. As I look back with a great deal more experience under my belt, I realize that I should have done things a bit differently. I could’ve gotten more info on the route, for one thing. I should have had a bit more experience going into such a climb, i.e., I should have gone with someone who could show me the way instead of bringing a friend along whom I could have gotten seriously injured. Finally, and most importantly, I should’ve self-rescued. Climbers must learn to rely on their own skill far more than we did on this trip. We could have rappelled from our position. We had enough gear, I think, that we could have ditched a piece here and there to get ourselves down at least to a safer altitude. We could’ve brought a bivy sack or more food. There are many things that could’ve happened that would have avoided a call to search and rescue.

The most important thing is that I learned from my mistake and have since been far more careful in the mountains. I am eternally grateful to the volunteers of those two search and rescue groups; they were great. They told us we did the right thing in calling them. They said there are two types of climbers in this world, those who have been rescued at one point and those who will need to be rescued. But if I ever need a rescue again, it will be a self-rescue — I have learned my lesson.